Harness Variety & Function

What is wrong with the harness in the photo above?

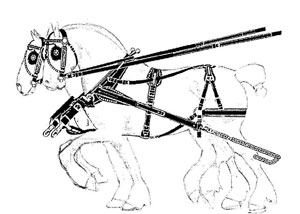

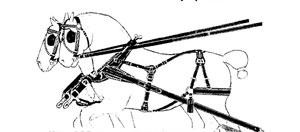

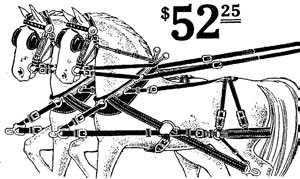

In Steve Bowers’ book Farming with Horses, Bowers states, “According to my research, about 80 percent of the draft-type harness used are (the Box Breeching or Western) style.”1 The Box Breeching or Western Style harness is also sometimes called a Bellybacker harness. This style of harness is illustrated in the diagrams on the opposite page. If Steve Bowers found that 80% of harness is the Box Breeching style, then most of us, when we think about harness, probably have a mental image of this sort of harness in our minds. The harness in the photo above doesn’t even come close to matching this image. Yet the harness shown in the oat drilling photo is perfectly suitable for the job it’s doing. There’s nothing wrong with it.

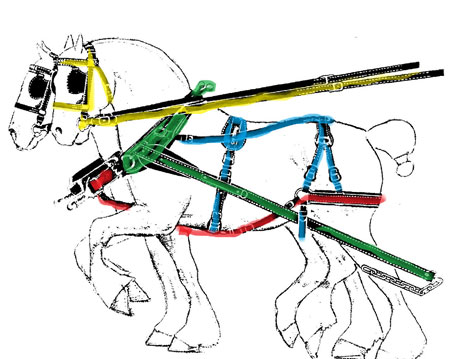

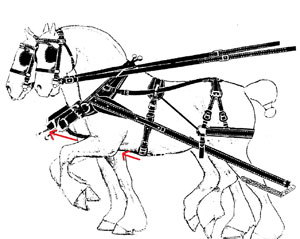

We can think of harness as having four distinct components:

- The Communication Component: to communicate with and direct the draft animal. The Communication Component is highlighted in yellow in the drawing. It consists of the bridle, bit and lines.

- The Draft Component: to accomplish the drawing or pulling of the load. The Draft Component is highlighted in green in the drawing. It consists of the collar, hames and hame straps, traces, and trace chains.

- The Stopping and Backing Component: to stop a load, slow down a load, or back up. The Stopping and Backing Component is highlighted in red in the drawing. It consists of the breeching band (sometimes called a britchen), quarter straps (sometimes called side straps or hold back straps), pole straps (sometimes called martingales), and breast straps.

- The Support Component: the portions of the harness necessary to keep the pieces of the other Components in their proper positions. The Support Component is highlighted in blue on the diagram. It includes the back pad (sometimes called a saddle) and back pad billets, the belly band and belly band billets, the spider (back straps, rump pad, hip pads and hip straps), lazy straps (sometimes called trace carriers), and crupper, if present.

The simplest harness is one with just the Control and Draft Components. Doc Hammill recalls, “Old timers that were my mentors told me about half-harness: collar, hames, traces. That’s all you really need to pull a load, as long as the load won’t roll forward to hit the animal. It’s a really basic pulling system. A lot of people don’t understand that that’s all you need to pull a load. When people are concerned about the weight of harness, depending on what they’re doing, they can have this sort of harness and do a lot of this type of work. It’s cooler, it’s lighter, there’s fewer things rubbing on the horse. If you look at stuff from third world countries, you’ll see an incredible amount of this sort of harness. It’s economical and it works.”

In rare circumstances, the Control Component can even be optional. Where there is an exceptional teamster or an exceptional equine, the equine can be worked loose-headed, without bridle and lines, maybe with just a lead rope tied up to the hames. Skidding logs is an example of a job that is occasionally performed loose-headed. Equines pulling ore carts in mines were also sometimes worked loose-headed.

Dale Wagner shared the following on the Rural Heritage Front Porch:

“Keep your harness as simple as possible. All that is really needed is a collar, hames and tugs. I have a picture of my grandpa taken about 1900. He has a four − up hooked to his freight wagon. Bridles, lines, collars, hames and tugs was all he had. No belly bands, back pads or britching. No dropper from neck yoke to the lead chain. He had to cross several coulees to go get groceries 80 miles away. He did have brakes on his wagon.”2

Dale’s grandfather was obviously an exceptional teamster who knew how to use brakes to help his horses do their job safely and comfortably. Doc emphasizes, “I certainly wouldn’t recommend making the choice to put a wheel team on a wagon without breeching, unless there was no other choice. It certainly can and has been done but there are potential safety issues. Also, with a four-up, only the back two (wheel) horses would be able to utilize breeching anyway, since the leaders aren’t connected to the tongue in a way that lets them hold the load back unless a false tongue is used.”

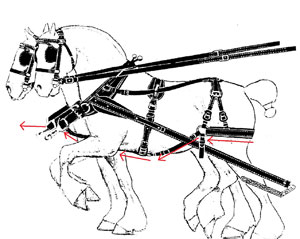

differ from the one in the photo on the opposite

page? Courtesy Samson Harness Shop, Inc.

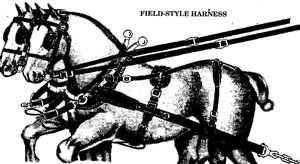

The Field-style, or plow harness, also does not include the Stopping and Backing Component. Yet it differs significantly from the harness in the oat drilling photo and from the half-harness that Doc describes. What are the functional differences?

The most obvious difference is the Support Component for the traces over the hips of the horse, which includes back straps, rump pad, hip pads, trace carriers, and crupper. What function do these additional pieces of harness serve? They keep the traces from getting tangled with the horse’s legs by keeping the traces up off the ground.

A disadvantage of trace carriers is that if they are adjusted too short, they can distort the angle of draft, which interferes with the efficient transfer of power from the horse to moving the load. The same problem can occur with a lazy strap on any style of harness that has them if they are adjusted too short. The photo of the single horse skidding a tire illustrates this problem. You can see that the trace is deflected upward where it passes through the lazy strap. To correct the problem, the lazy strap needs to be lengthened so that the line of the trace from hame to load is a continuous straight line, not broken as it is in the photo.

Doc shares, “When trace carriers are too short, the horse feels a downward pull on the rear quarters when under draft. Many horses will pull light loads in such cases but become balky with heavier loads. It’s common for trace carrier straps or lazy straps to not have enough adjustment available in them to pull loads on the ground properly. They typically end up being too short, as in the photo, so the horse feels a pull down on the hips. If the chain between the single tree and the tire was lengthened enough, the trace could theoretically be straightened out (the singletree would be lifted into the air in draft), making the line of draft straight, but for draft advantage and maneuverability we want the load we are skidding close to the horse.”

Another obvious functional difference between the harness in the oat drilling photo and the plow harness is that the plow harness is set up to be a team harness that can be hitched to and steer a tongue, so there is a breast strap. Though not all plow harnesses have a pole strap, the plow harness in the illustration does have one; it acts as a choke strap, buckling around the bottom of the collar and with a loop at the other end to allow the belly band to pass through it. It acts to prevent the collar from being pulled up. Yet this plow harness still differs from the Box Breeching/Western Style that is so common.

arrows indicate stopping forces you can reverse the

arrows to reveal backing forces.Courtesy Samson Harness Shop, Inc.

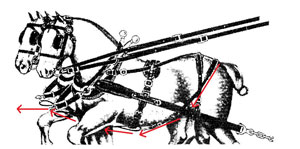

What the box breeching/Western style harness has that the plow harness doesn’t have is — surprise — the breeching. The breeching is part of the Stopping and Backing Component, which also includes quarter straps. The Support Component for the Box Breeching Harness includes the hip straps, rump pads and hip pads. In the case of a team harness of this style, the Stopping and Backing Component also includes the breast strap and pole strap.

The red arrows in the drawing of the Box Breeching or Western Style Harness indicate the forces exerted during stopping. If a team of horses on a tongue is asked to slow down or stop a load, when the horses decelerate, the tongue and its load have forward momentum, so the tongue pushes forward on the neck yoke which pulls forward on the breast strap, which pulls forward on the pole strap, which pulls forward on the quarter straps, which pull forward on the breeching, against which the slowing horses hold steady or exert more pressure until their speed and their load’s speed is equalized.

For backing, the red arrows in the drawing would be reversed. From a standing position, if a team of horses on a tongue is asked to back, they push into the breeching band, which pulls on the quarter straps, which pulls back on the pole strap, which pulls on the breast strap which pulls on the neck yoke attached to the tongue. In the case of a single horse in shafts, the backward pressure on the breeching band pulls back on the two hold back straps which are attached to each of the shafts of the load.

Looking back at the plow harness and the harness in the photo at the beginning of the article, you can see that indeed they do not have a fully functioning Stopping and Backing Component because they lack the breeching and associated Support Components. Doc notes, “The plow harness does have a semblance of a Stopping and Backing Component that I think a lot of people rely on. The pole strap hooked to the neck yoke and belly band is expected to serve the function of a stopping and backing system. There’s some capability there, but it’s not very good.”

We know that people use harnesses without effective stopping and backing capabilities on wheeled loads, as Dale Wagner’s grandfather did, but using them in that way requires a brake or some other mechanism to hold back the load. Even some plows that have wheels and are used in hilly country must be operated skillfully if harness without breeching is used; teamsters must be prepared to drop the plow in the ground to slow it down for instance. Doc shares, “If you don’t have breeching, you will need some kind of solution to keep the load from running up into the horses, and you’d better know how to operate it and be ‘up in your riggin’ at all times.”

Courtesy Samson Harness Shop, Inc.

A slight variation on the Western Style or Box Breeching Harness is the Butt Chain or Short-Trace harness. The name “butt chain” comes from the fact that the chain on the trace disconnects from the trace at the butt rather than at the heel, as in heel chain traces. Where the chain meets the trace, there is a hook on the trace to accept the butt chain. A Western Style/Box Breeching Harness can be converted to a Butt Chain Harness by swapping out the traces and modifying the trace carriers.

Doc shares how helpful he finds this sort of harness in logging applications. “My butt chains have a ring at one end, and I have singletrees specifically for butt chains that have rings instead of hooks. I thread the chain link end of the butt chains through the singletree rings, and, when the rings on the butt chains come up against the singletree rings, they won’t go through, and they cannot come unhooked. To hitch the horses to the singletrees, the ends of the butt chains are hooked to the hooks on the end of the traces. When the horse or team walks off without a load, the singletree or team rigging drags behind with the chain’s full length where they won’t hit the horse’s heels. When hitching to a load (for maximum draft advantage and lift), I shorten the butt chains by simply pulling the butt chain rings forward and hooking them onto the trace hooks. This quickly and easily doubles and shortens the butt chains by half for pulling the load. No counting links or extra chain dangling or dragging. When dropping the load, I don’t have to go clear to the ground to lengthen the chains to drag the rigging back on the ground empty. I simply pull the rings off the trace hooks at knee height, and the chains lengthen as the horses walk away.”

Doc continues, “If I’m hooking to singletrees with hooks instead of rings with this sort of harness, I hook the butt chain rings to the singletree hooks, and then hook to the trace hooks with whichever chain links give me the right adjustment.”

This harness also allows the trace chains to be left attached to the singletree or vehicle. Leaving the trace chains elsewhere makes the harness lighter. Doc recalls, “One of the reasons this type of harness was popular with the big hitches in wheat country and the big plow hitches was that the butt chains were separate from the harness. Say you had a combine hitch with as many as 33 horses on it. All the chains could be left on the singletrees. You could get everything set the way you liked it, then when you unhitch at end of the day, you unhook the chains from the trace, and leave them with the singletree. You don’t have to take that weight on and off with the harness. When you hitch in the morning, all you had to do was hitch on the end link; you didn’t have to count any links to drop and remember how many to drop for each horse.”

Another advantage of this type of harness is that the traces are shorter and are less likely to be stepped on by the horses or to get soiled in muddy conditions. Doc adds, “Also, there’s no hooking trace chains up on the hips when unhitching and taking them down to hitch up. I just pull the chains off the trace hooks and drop them.”

In logging applications or other situations where horses are wearing calked shoes, the short traces being up out of the way keep the traces from being stepped on and damaged by the calks. In addition, when this type of harness is hung up for storage, the traces hang straight as opposed to with a long tug harness, the traces tend to bend in storage, especially if hung on a single hook. A disadvantage of this type of harness is that if horses are moved between several pieces of equipment, it can be easy to lose track of the butt chains or lose them. Having multiple chains, one set for each piece of equipment, is one possible solution to the problem.

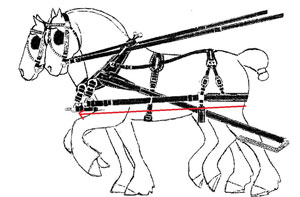

attached to backpad instead of pole strap. Red

arrows show force of slowing wagon on harness

and horse. Courtesy Samson Harness Shop, Inc.

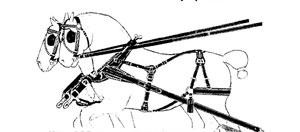

The photo above shows a team hooked to an end-gate seeder; the team is wearing Western/Box Breeching style harness. What is unusual about the way the righthand horse is harnessed?

It appears that the quarter strap on the horse is hooked up to the backpad instead of down to the pole strap where it would normally be as part of the Stopping and Backing Component. Could it be that someone forgot to fasten this strap when they were harnessing? Or perhaps the horses were muddy, and the teamster didn’t want to soil the strap? Since the ground appears to be extremely level, perhaps the teamster felt that the weight of the wagon and the roughness of the ground were sufficient slowing and stopping forces.

In extreme cases with using harness in this way, the belly band could come up behind the horses’ elbows. The red arrows in the harness diagram above illustrate the force of a slowing wagon on the harness via the tongue. Without the quarter straps attached to the pole straps, the horses are forced to take the strain of slowing, stopping, or backing the load on the collar and back pad/belly band system which could jeopardize the comfort of the horses and therefore jeopardize safety.

The above shows a team hooked to a lead and a trail wagon. Is the team wearing Western/Box Breeching harness or plow harness? The team is wearing plow harness, which means it doesn’t have breeching, which is part of the Stopping and Backing Component. These wagons represent a pretty heavy load. The teamster may be compensating for the lack of Stopping and Backing Component in his harness by the levelness of the ground, feeling he can ease the wagons to a stop. He must also not need backing power.

Mac, a visitor to the Rural Heritage Front Porch, explains his reasoning for using plow harness in a similar situation:

“I’ve got two sets of harness: one wagon harness and one for plowing. I'd say I've pulled the wagon more with the plow gear than I have with the wagon harness. I don't like adjustments and I don't like heavy either. I use my plow harness for everything except going to town in the buggy or wagon. It’s my experience when you get up at 5 and go to the field, you don't want to be making adjustments in the dark. Chuck the gear on and go.”3

Doc observes, “Obviously Mac is capable of taking care of his horses and making sure he uses the brake so that he never lets the wagon run into the horses. I once heard Neil Dimmock say that brakes cause more problems than they solve because they make people think they can stop their horses if they run away. Neil said, ‘You don’t need brakes; the brakes are between a horse’s ears.’ While plow harness on wagons may work for experienced teamsters like Mac and Neil, I still advise my students that they need a fully functioning Stopping and Backing Component including breeching, if they’re going to pull wheeled loads safely and comfortably. Brakes are meant to help hold back vehicles and equipment, not stop horses. On my harness, the Stopping and Backing Component can be quickly and easily removed by simply unsnapping the hip straps from the hip pads and unbuckling the collar straps to detach the pole straps. It’s there when I need it and gone when I don’t. ”

JC Allen photo.

The photo above shows a three-abreast on a cultivator. The horses are wearing a type of Box Breeching/Western Style harness. However, on the near horse the harness has a feature that is not common on this style of harness. There is a hip drop with a lead line snapped from there to a hame ring. What function might this feature serve? In many towns during the horse era, there were laws requiring that horses that were driven into town must be able to be tied at a hitching rail. Harness makers provided the optional hip drop on harness for tying up a lead line to facilitate compliance with such laws.

You may also notice that this harness is fancier than it needs to be for farming. It has “spots” in many places (metal ornamentation), has fancier hames than in the previous pictures, and has terrets on the backpad for the lines to pass through. Perhaps the farmer always wanted his horses to look nice when working, or perhaps he was a breeder and needed his breeding stock to be shown at their best.

One other difference between the harness in the photo at lower left and typical box breeching/Western style harness is that back straps aren’t visible running from the hames through loops on the back pad to the rump pad. The function of the back straps is to keep the collar from falling forward when the horse puts its head down. Perhaps there is a strap not visible here from the top of the collar to the rump pad that serves this function.

Doc adds, “Most Western style harness has double back straps angling from the hames to the rump pad to keep the hip plate from sliding sideways off the hips. On single back strap style harness, you need a crupper to stabilize the hip plate. I would guess that these horses were most likely wearing cruppers.”

Photo courtesy Doc Hammill.

A slight variation on the Western Style or Box Breeching Harness is the Butt Chain or Short-Trace harness. The name “butt chain” comes from the fact that the chain on the trace disconnects from the trace at the butt rather than at the heel, as in heel chain traces. Where the chain meets the trace, there is a hook on the trace to accept the butt chain. A Western Style/Box Breeching Harness can be converted to a Butt Chain Harness by swapping out the traces and modifying the trace carriers.

Doc shares how helpful he finds this sort of harness in logging applications. “My butt chains have a ring at one end, and I have singletrees specifically for butt chains that have rings instead of hooks. I thread the chain link end of the butt chains through the singletree rings, and, when the rings on the butt chains come up against the singletree rings, they won’t go through, and they cannot come unhooked. To hitch the horses to the singletrees, the ends of the butt chains are hooked to the hooks on the end of the traces. When the horse or team walks off without a load, the singletree or team rigging drags behind with the chain’s full length where they won’t hit the horse’s heels. When hitching to a load (for maximum draft advantage and lift), I shorten the butt chains by simply pulling the butt chain rings forward and hooking them onto the trace hooks. This quickly and easily doubles and shortens the butt chains by half for pulling the load. No counting links or extra chain dangling or dragging. When dropping the load, I don’t have to go clear to the ground to lengthen the chains to drag the rigging back on the ground empty. I simply pull the rings off the trace hooks at knee height, and the chains lengthen as the horses walk away.”

Doc continues, “If I’m hooking to singletrees with hooks instead of rings with this sort of harness, I hook the butt chain rings to the singletree hooks, and then hook to the trace hooks with whichever chain links give me the right adjustment.”

This harness also allows the trace chains to be left attached to the singletree or vehicle. Leaving the trace chains elsewhere makes the harness lighter. Doc recalls, “One of the reasons this type of harness was popular with the big hitches in wheat country and the big plow hitches was that the butt chains were separate from the harness. Say you had a combine hitch with as many as 33 horses on it. All the chains could be left on the singletrees. You could get everything set the way you liked it, then when you unhitch at end of the day, you unhook the chains from the trace, and leave them with the singletree. You don’t have to take that weight on and off with the harness. When you hitch in the morning, all you had to do was hitch on the end link; you didn’t have to count any links to drop and remember how many to drop for each horse.”

Another advantage of this type of harness is that the traces are shorter and are less likely to be stepped on by the horses or to get soiled in muddy conditions. Doc adds, “Also, there’s no hooking trace chains up on the hips when unhitching and taking them down to hitch up. I just pull the chains off the trace hooks and drop them.”

In logging applications or other situations where horses are wearing calked shoes, the short traces being up out of the way keep the traces from being stepped on and damaged by the calks. In addition, when this type of harness is hung up for storage, the traces hang straight as opposed to with a long tug harness, the traces tend to bend in storage, especially if hung on a single hook. A disadvantage of this type of harness is that if horses are moved between several pieces of equipment, it can be easy to lose track of the butt chains or lose them. Having multiple chains, one set for each piece of equipment, is one possible solution to the problem.

JC Allen photo.

has a different Stopping and Backing Component.

The red arrows show the forces when the horses

are asked to slow or stop a load.

Courtesy Samson Harness Shop, Inc.

A variation on the Stopping and Backing Component of the western style harness is called Yankee or Hip Breeching (sometimes also called Mormon harness). “The advantage of the Yankee brichen is that the weight of the load when the horse is backing pushes down on the horse's rump. This provides better traction than the box-type brichen, which tends to push the horse forward.”4 Note that Yankee breeching works well for teams but not for a single horse in shafts.

The Yankee/ Hip Breeching Harness requires a variation in the Support Component as well. There is a crupper to which the Yankee Breeching is attached to keep the breeching in place just above the tail head. In the diagram of the Yankee/Hip Breeching Harness, the red arrows indicate the forces when the team is asked to slow or stop a load. When the horses slow, the momentum of the load pushes the tongue and attached neck yoke forward which pulls the breast strap and the pole strap forward, which pulls down and forward on the quarter straps, which pulls down and forward on the breeching, against which the horse pushes. Rural Heritage Front Porch visitors make these comments about Yankee or hip breeching harness:

- "The (breeching) crosses above the animals' tail on the croup rather than below across the hams. I like it because there is less movement closer to the joint so there is less chance for chafing. The line from the croup to the neck yoke passes through the center of gravity of the animal, and there is a little less leather involved." 5

- “This is what I use and I like them. They seem to be lighter and you don't have any straps under their butt to get pooped on. Also, when stopping or backing, it pulls down on their rear end instead of pushing on the back of their legs.” 6

- “We use the Yankee breeching a lot. It is lighter and cooler, but we use it because mules seem to be able to back a heavy load and hold better. Works well in Tennessee hills.” 7

- “This design is excellent if you back or hold heavy loads as it uses the most muscular part of the butt and can never pull the legs out from under when the britchen is dropped too low. And yes, it does eliminate manure on the britchen although it does require a crupper, so that needs to be kept

clean.” 8

Similar to concerns about defecation on breeching, Doc bought Yankee breeching to replace the box breeching on one set of his harness because of issues with urination. “Every time my mare Misty urinated in harness, she hit the breeching and splattered urine all over her hind legs. Not so with Yankee breeching. It didn’t matter how high or low I adjusted the box breeching, she would hit it. The final decision to invest in the Yankee breeching was out of consideration for Misty.”

Doc continues, “On the steep mountain roads of the west, this sort of harness was common. It is also popular for bobsleds because the downward pressure on the hips provides better traction for horses holding back loads on snow and ice. I even had a man tell me that an old timer told him that a horse could back as much with a Yankee breeching as he could pull, not so with a box breeching.”

A combination of box breeching and Yankee/Hip Breeching is called basket breeching. According to Dale Wagner, “The Kitteredge ranch used both hip and butt breeching together on buck rakes. This was because after being on a buck rake for a long time, when you ran a tooth in the ground, the horses had a tendency to fly back and break breeching, especially when it had some age on it."9

Doc shares, “Jerry Lee from Oregon tells of his grandfather using basket breeching on his big lumber wagon for maximum hold back and backing capability for big heavy loads. Also, if one system failed the other would maintain function.”

Courtesy Samson Harness Shop, Inc.

A departure from the Box Breeching/Western Style harness is the Y-Back, Dakota, or Market Tug Harness. This harness type lacks a back pad/saddle, and the back strap is broken into two pieces, one from the rump pad to the top of the market strap and one from top of the market strap to the hames. The name “Market Tug” for this harness may be confusing to some people because the terms tug and trace are often interchanged. In the name “Market Tug Harness,” tug refers to the harness pieces from the hame to the rump pad; there are two pieces, a shoulder strap and a back strap, instead of one, the back strap as in the Box Breeching harness.

In the Box Breeching/Western Style harness, when the horse lowers its head, it pulls the collar forward, which pulls the breeching up. In the Y-Back harness, when the horse lowers its head, the breeching stays in place. This harness was commonly used in the large grain-harvesting hitches of Oregon and Washington where hitches of 33 mules, horses or combinations of both were common. These hitches typically had five tiers of six abreast with three abreast in the lead. The logistics of feeding and watering the equines during the work day were significant. Often the horses or mules were left hitched together in their rows for feeding and watering, so it was important for the efficiency of the work that their harnesses stay in place. The Y−Back harness was a significant enabler of efficiency because it allowed the equines to be fed and watered in harness without harness adjustments needing to be made afterwards since the collars weren’t pulling the breeching forward with the back straps.

When working, horses tend to sweat first under the backpad. The Y-back harness is often preferred in hot, sunny locations because it lacks a backpad. The absence of the backpad also reduces the weight of the harness by a small amount.

Stopping and Backing Component. The red arrows

indicate the forces when slowing or stopping a load.

Courtesy Samson Harness Shop, Inc.

Like the Yankee/Hip Breeching Harness, the Sidebacker Harness has a different Stopping and Backing Component from the Box Breeching/Western Style Harness. (The Sidebacker is also known as the Boston Backer Harness.) The breeching is connected straight forward to a jockey yoke that then connects to the neck yoke. Note how the forces, indicated by the red line in the drawing, are more direct when the horse is backing in this harness than in the Box Breeching/Western Style harness.

Doc observes, “It’s very easy to convert conventional Box Breeching harness to this style; you don’t have to buy all new. Note how the breeching and hip straps are the same here as they are in the Box Breeching harness. The difference is between the breeching ring and the neck yoke connection. Rather than the breeching connecting to a pole strap with quarter straps, we instead have side straps. We don’t have a pole strap; the side straps replace both the quarter and pole straps. We don’t have a breast strap either; it’s replaced by a pair of jack straps or jockey straps. Jack straps suspend a jockey yoke (also called twin yoke or double yoke) from the hames, replacing the breast strap as the system that holds the neck yoke and tongue up. When my back was real bad, it was a lot easier to harness with this harness. The only thing I had to bend over to do was buckle the belly band, not quarter straps one on each side. When your back hurts, it’s a big help to not bend over so often.”

Rural Heritage Front Porch visitors make these comments about the Sidebacker Harness:

- “I use the Sidebacker harness and love it. I was using harness with the quarter straps and pole strap. One day while hooking up to a stiff tongue wagon one of my mules got his hind leg caught in a quarter strap while stepping across the tongue. I live in the mountans. Use them a lot for holding back. Sometimes the pole strap would gall the inside of their front legs. Sidebackers don't do that.” 10

- “Two advantages to the Sidebacker are working pregnant mares without the up pressure of the belly backer's quarter straps and less chance of a wreck when horses are trying to knock insects off their bellies in fly season.”11

- “Never get a more complicated or heavier harness than you need. Buckrake, header, or push binder is about the only place you need a Sidebacker style. If you have a tongue, the belly backer is all you need.” 12

- “The disadvantage of a Sidebacker is the tongue can raise up high as the horse’s back. I think it comes down to what you are used to.” 13

- “(When) horses were commonly used for farm work around here (especially in steep hills) most used Sidebacker harness and D-ring traces. They still used the pole straps and martingales hooked into the belly band to hold the neck yoke at the right height. The jockey yokes sat behind the neck yoke instead of on top of it and were only responsible for holding back the load and not holding up the pole. I'm assuming this was to stop the pole from lifting. In my opinion, this is getting the best of the both worlds.” 14

One feature of the Sidebacker harness shown in the drawing above is a ring on the belly band billet through which the side strap passes. This ring serves two functions. First, it holds the side strap up in place. Second, it acts to prevent significant upward motion of the tongue above the belly band billet.

Doc adds, “They used the Sidebacker with breast strap and pole strap on a lot of the logging sleds in western Montana in the old days. If a horse in the pole team fell down, it would tend to be pulled along rather than spill out of the harness and get run over by the sled. There was a basket of straps down the sides, under the belly, and between their front legs to drag them along until the sled stopped.

“One disadvantage of the Sidebacker is that it can allow the tongue to swing side to side more than the bellybacker depending on the breast strap style. My dump rake on a rough field. The mower wasn’t too bad, but on the dump rake, if one wheel hit an irregularity, it tended to swing the tongue sideways. The first morning the rake tongue was hitting the horses in the front legs, so I took the foam pad that I was sleeping on and wrapped it around the tongue. That night I went home and got quarter straps, breast straps, and pole strap and converted back to a bellybacker style. There was no problem whatsoever then.”

a different Draft Component as well as a different

Stopping and Backing Component. The red lines

show the forces when slowing or stopping. The

green line shows how the trace can move up and

down without changing the angle of draft at the collar.

Courtesy Samson Harness Shop, Inc.

The New England D-Ring Harness has a different Draft Component compared to all the other harnesses discussed so far. It is designed to keep the angle of the trace at the collar fixed at the ideal angle of 90 degrees while the position of the trace attached to the load can change. The intent is to maximize the transfer of power from the horse to moving the load. Some D-ring harnesses have more range of motion than others, depending on the room on the ring for the leather to slide.

In addition, this harness is intended to transfer the weight of the tongue to the backpad rather than having it pull down on the collar as it does with the other harness designs. This feature is accomplished by adjusting the traces and neck yoke so that the tongue is suspended rather than a dead weight attached at only the neck yoke, as in the Box Breeching harness.

Disadvantages often cited about this harness include that it is heavy, and it is hotter for the horses in warm weather. It also requires very specific adjustments to work correctly.

Rural Heritage Front Porch visitors have shared the following about D-Ring harness:

- “I've used D-ring harness for 7 or 8 years now and would be hard-pressed to go back to standard harness. I agree … that they really do make a difference at the end of a long day in the field or woods.” 15

- “The only problem that I have ever had with a D-ring is that they are heavy. My Suffolks work on many different kinds of equipment and the point of draft can change without adjusting the harness. Working a heavy load in the hills of Vermont, a D-ring with jockey yokes keeps the horse square with the pole when being pushed down a steep hill …. To be set up right it needs to be tight from the jockey yoke to the evener to have the pole weight on the back pad.” 16

1917, Richland Special New England Farm Harness.

Courtesy Samson Harness Shop, Inc.

A 1917 harness catalog shows a New England Harness (shown in drawing at left). How does this harness differ from the New England/D-Ring harness previously shown? The 1917 version lacks a backpad. What is the implication of this harness not having a backpad? The function of the backpad in modern-day New England harness is to accept the weight of the pole. The 1917 version of this harness was apparently expected to be used in an application where there wasn’t pole weight, perhaps with the types of poles/ tongues that are self-supporting. Doc comments, “Even though the trace is free to change its angle up or down behind the ring on a D-Ring Harness, one should be careful to avoid extremes. A trace pulling at a more upward angle than ideal behind the ring can apply force upward on the belly band, and a trace pulling at a more downward angle (less common) can pull down on the backpad. Either of these can cause discomfort for the horse and, therefore, can potentially create safety issues. An important purpose of the belly band on any harness is to maintain a 90 degree angle of draft on the collar if the traces pull up too high. A straight line of draft from hames all the way to the hitch point, and the proper 90 degree angle of draft off of the hame, is always preferable.”

as well as different Stopping and Backing and

Support Components.

Norwegian harness is considered by some to be the inspiration for New England/D-Ring harness. As with the New England harness, Norwegian harness incorporates a different Draft Component, and it also has a different Stopping and Backing Component as well as a different Support Component. For a detailed discussion of Norwegian Harness, see “A Better Harness?” in the Holiday 2005 issue of Rural Heritage.

Like the New England harness, Norwegian harness is designed to keep the angle of the trace at the collar fixed at the ideal of 90 degrees. Unlike the New England harness, the trace in the Norwegian harness ends at the ring, and all loads are attached there, either via traces for skidding or via shafts (teams are worked in a double shaft set-up). Also unlike all the harnesses previously discussed, the Norwegian harness features an integrated collar and hames with adjustments top and bottom to accommodate changes in the shape of the neck over the course of the seasons.

The Stopping and Backing Component differs from the New England in that there is an extra padded strap (ring girth) under the belly designed to hit behind the elbows in case the breeching system for stopping isn’t sufficient. The Support Component differs in the backpad. Because the backpad is intended to take significant strain from the load, it is a bow with two separate pads on either side of the backbone behind the withers. Another difference from the New England harness in the Support Component is that the belly band doesn’t go to/through the ring, so that the ring is less congested and can be set farther forward to accommodate the ring girth.

With the exception of the Norwegian Harness, the various harness types mentioned above are those commonly in use today. They are depicted in books about draft horses and included in harness catalogs. However, there are several harness types that do not show up in these places because the jobs they helped accomplish no longer exist. Special harnesses, for instance, were used for stagecoaches, for hauling freight and for express deliveries, activities that are no longer provided with horsepower except in re-enactment circumstances. How did these harnesses differ in the various Components? We’ll explore that topic in a future article.

Doc always emphasizes safety, function and comfort when talking to clients about harness. “Safety and comfort go together. Most of the behavior problems we see with horses are caused by some sort of physical discomfort. Some say it’s as much as 80 percent, with the remaining 20percent of the problems caused by something psychological.”

One Rural Heritage Front Porch visitor aptly concluded:

“(There) are as many styles of harness as there are harness makers and at least that many reasons one is better than the other.” 17 It’s up to us as teamsters to understand how the various Components of harness work together so that we can choose the right harness type for the jobs we have to do with our horses.

- How would you rate the breeching adjustment in the harness drawings in this article? Doc observes, “In all cases except the Yankee/Hip Breeching, the breeching is set well below the point of the buttock. I’d like to have the artist raise those breechings up at least the width of the breeching band and in some cases even more.”

- How would you rate the trace angle in the harness drawings in this article? Doc notes, “In nearly all cases, the angle of the trace at the hames isn’t 90 degrees, so it isn’t optimal for converting the horse’s push into the collar into forward movement. When the angle differs from 90 degrees, there is also the potential for draft activity to damage the shoulder. Even in the two D-ring drawings the angle isn’t optimal. Regardless of the style of harness, it is extremely important that the traces leave the hames at a 90 degree angle from the line of the hame/collar/ shoulder. Otherwise, the forces of pulling a load can have potentially damaging consequences on the animal’s shoulders. ”

Doc concludes, “Unfortunately, incorrect angles of draft, broken lines of draft, and breechings set way too low are very common in diagrams, harness catalogs, and photographs. They provide bad examples for folks who may not know better. I feel those of us with some depth of understanding have a responsibility to share what we have been fortunate to learn and experience to the benefit of our fellow teamsters and for the welfare of the animals.”

![]()

- 1Bowers, Steve and Marlen Steward. Farming with Horses, MBI Publishing Company, St. Paul, MN, 2006, p. 10.

- 2Response by Dale Wagner, "Disadvantages to the D-ring Harness?" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/15722.htm, timestamp 2012-01-27 02:16:17

- 3Response by Mac,"Disadvantages to the D-ring Harness?" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/15722.htm, timestamp 2012-02-03 00:26:11

- 4http://www.stitchnhitch.com/optattachm.htm

- 5Response by Bob E, "Yankee Britchen" at https://ruralheritage. com/messageboard/frontporch/15000.htm, timestamp 2011-07-25 09:30:57

- 6Response by Marshall, "Yankee Britchen" at https://ruralheritage. com/messageboard/frontporch/15000.htm, timestamp 2011-07-25 10:04:31

- 7Response by Mark, "Yankee Britchen" at https://ruralheritage. com/messageboard/frontporch/15000.htm, timestamp 2011-07-25 13:25:48

- 8Response by Stitch N Hitch Harness Shop (signed Mari Leedy), "Yankee Britchen" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/15000.htm, timestamp 2011-08-01 18:02:13

- 9https://albrechtsanimals.typepad.com/understanding_harness/ 2013/03/breeching-basket.html

- 10Response by TLR, "Sidebacker" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/9450.htm, timestamp 2007-07-27 14:06:54

- 11Response by Neal in Iowa, "Difference between a belly-backer and side-backer harness" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/14016.htm, timestamp 2010-12-17 17:09:40

- 12Response by Dale Wagner, "Difference between a belly-backer and side-backer harness" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/14016.htm, timestamp 2010-12-17 10:35:50

- 13 Response by KM, "Difference between a belly-backer and sidebacker harness" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/14016.htm, timestamp 2010-12-18 08:52:59

- 14Response by Chris F., "Difference between a belly-backer and side-backer harness" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/14016.htm, timestamp 2010-12-18 18:36:50

- 15Response by aherzog, "Disadvantages to the D-ring Harness?" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/15722.htm, timestamp 2012-01-31 10:12:01

- 16Response by Peter, "Disadvantages to the D-ring Harness?" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/15722.htm, timestamp 2012-02-02 15:46:18

- 17Response by KM, "Disadvantages to the D-ring Harness?" at https://ruralheritage.com/messageboard/frontporch/15722.htm, timestamp 2012-01-25 22:25:18

Doc Hammill, DVM, offers instructional videos, workshops, private instruction, and phone/online coaching year-round on driving, working, and training horses in harness: www.dochammill.com.

Thank you to Bernie Samson ofSamson harness Shop, Inc. for his consultation on this article.

This article appeared in the June/July 2013 issue of Rural Heritage magazine.