Hitching Safely

One of many workshops that Doc Hammill conducts each year teaches the students’ current capabilities but will be important later in their learning process – things such as hitching by yourself without a place to tie, hitching young or inexperienced horses, hitching horses in a team for the first time and hitching to and driving something unfamiliar and potentially frightening to the horse or horses.”

Photo courtesy Cathy Greatorex.

Hitching and unhitching is a time of great vulnerability. “We really need to have horses that stand reliably, and until people’s skill and experience is very high, they need to have their horse or horses tied up while hitching and unhitching, or at least have someone to hold and help manage them (a header),” says Doc. “When we start doing it alone without a place to tie or a header, the horses really have to know to stay put, and the person needs to not mess around. We just need to pay attention and get the job done without delay or distraction. The students in this workshop saw firsthand how dangerous it can be if horses become distracted, anxious, fearful, or move around when only part way hitched.”

Doc continues, “It’s really important to have a very specific, well understood and consistent hitching and unhitching technique so that we can execute it precisely and promptly. We need to hitch and unhitch the same way every time to develop a consistent, familiar routine. In addition, we should strategically pre-position the vehicle or equipment we’re hitching to. And we need to have a clearly thought out ‘escape plan’ each step of the way so we can get ourselves and/or our horses out safely in case something does go wrong.”

Pre-positioning the Vehicle

For Doc, pre-positioning the vehicle strategically typically means putting it where the horses will be facing a direction they don’t especially want to go so they’re not inclined to take a notion to leave. “I don’t recommend pointing the horses toward the barn or the hitch rail or other horses in the herd. I do try to use a physical or visual barrier of some sort; I don’t like a lot of open space in front of them, especially for horses with limited experience.”

Ground-driving the team to a strategically prepositioned vehicle provides all sorts of opportunities for assessing readiness to hitch. “It’s a test drive. I get to see if everything is working right. Are my lines adjusted right? Will the horses in fact start, stop, stand, and back when I ask? Do the horses look like they’re the proper distance apart on the bits for the neck yoke and doubletree?

“Many times horses are anxious or in a forward mood or mode when we hitch, and they know we’re ready to go, so a lot of times just to counteract that forward energy, the first thing I do is to back a few steps, both ground driving and when hitched. When I’m harnessing in the barn, I back them up into the alley and purposely stop for awhile and wait while getting them to quit looking towards the door. Then I gee them 90 degrees then stop and wait. Only when they’re clearly relaxed and waiting on instructions and not interested in their own agenda do we go out the barn door.”

The Teaching Moment

The lesson that turned into an extreme teaching moment was how to hitch and unhitch when we’re alone and don’t have a place to tie the horses. Doc was demonstrating hitching to a wagon with a team of calm, reliable horses. The weather was changing often and quickly that day, and unbeknownst to Doc, a thunderhead was approaching from a direction where it was hidden by a hill and trees. Violent lightning began to strike suddenly nearby, with loud claps of thunder. Doc had just started hitching and had hooked the neck yoke to only one horse when explosive lightning repeatedly struck nearby, followed by deafening thunder. Doc was already trying to unhook the neck yoke when the other horse jumped sideways and knocked its partner off its feet.

“I don’t know how many thousands of times I’ve hitched horses and mules in the six decades since I started driving, but this was the first time I’ve ever had anything like this happen while hitching. In hindsight it wasn’t really much of an incident; it was more of a close call,” says Doc, “but it could easily have been disastrous”. His students were unanimous in their appreciation for how calm Doc remained and how he gently and efficiently managed the horses, both physically and psychologically, to a safe and minimally stressful outcome. Student Brad Peterson shares, “Doc knew exactly what to do so quickly and so calmly. The horses stayed relatively calm because they felt that from Doc; they knew they needed to just stop and stand while he made things right.”

In addition, the students also experienced how Doc managed “people reactions and behavior” at the same time he was calming, controlling, and untangling the horses. The students’ nervous energy, talking amongst themselves, and attempts to help started to add tension to an already difficult situation. “I signaled the students to be quiet and asked them to relax, take their energy down, and stop moving around while I was holding and calming one horse that wanted to get away, unhooking harness to get them apart, and quieting and comforting the horse that couldn’t get up,” says Doc. “It’s very natural in such situations for people to become upset and adrenalin charged, making things worse in their efforts to help.”

“Over the years there have been many times when my intention was to hitch up, but instead I abandoned the idea,” reflects Doc, “either because I judged the animals not well enough trained in general, or not prepared well enough for hitching specifically, or not in a frame of mind to be hitched safely at that particular time. It is imperative that they stand still in a quiet, comfortable, relaxed way to be hitched safely.” Having a horse or horses move when part way hitched or part way unhitched creates one of the most potentially dangerous situations that can happen.

Several important things contributed to the safe outcome from this extreme event. First, Doc had a strong relationship of trust, respect, and leadership with his team; he knew they were extremely well-trained and experienced and that they normally listened and responded to him well.

Next, Doc had made several changes to the typical hitching gear and harness to minimize chances for equipment failure or wrecks. (See “Preventing Wrecks” in Rural Heritage volume 37, number 2, April/May 2012, and the article “10 Common Wrecks with Driving Horses” on Doc’s website for complete details.) Over the years, he has heard enough stories of wrecks to know that taking the time to make these changes has prevented problems from occurring.

In addition, Doc had followed his step-by-step process for hitching so he knew exactly what had been done and what hadn’t when it came time to extricate the horses from their predicament. If he hadn’t been so rigorous about following his process, he wouldn’t have been as able to help his horses as quickly and quietly as he did.

Finally, because Doc had followed his process carefully, he also knew without thinking what the escape plan was at the point when the incident occurred. Because he was following a procedure that he knew well, he was able to successfully unhook the neck yoke as the falling horse was going down. It’s much easier to anticipate problems and consider escape routes when things are calm than to have to figure everything out in the crisis of the moment when something happens.

Of course, just because Doc was able to extricate the horses didn’t mean that was the end of the story. The students got to see what he did to calm and evaluate the horses after the mishap. “After I got the tangled harness off the downed horse and he was able to get up, I spent a lot of time rubbing him and talking to him, making sure he was alright both physically and mentally.” The storm had passed just as quickly as it came, and the horses were again relaxed and comfortable so they were led to the barn. After some quiet time, Doc’s partner Cathy and the students groomed and re-harnessed the horse that went down while Doc prepared to test the other one by ground driving it single. “My hope was to finish with a positive driving experience for each horse, but only if they could stay comfortable and handle it. I didn’t want them to associate acting fearful or misbehaving with getting out of harness or work, but I didn’t want to cause them further anxiety either.

“We used a very specific set of baby steps to test them out to see if any lasting psychological damage had been done. I started by ground driving one and then the other single. We left the barn and ground drove directly to the wagon, just as we had done an hour before with them as a team. The wagon was in the same spot as before. I drove them single because I wanted to observe each horse’s personal reaction to the wagon and the location of the incident. In turn, I drove each one up to the wagon tongue and stopped to let them check it out. Both horses checked the tongue out by touching and examining it with their lips, but neither seemed the least bit concerned about the wagon or the location. As they were examining the tongue I rattled the metal double tree and single trees with my foot to observe their reaction to the sudden noise. Neither horse reacted to it. After driving each of them single around the barnyard with lots of stopping, standing, and backing up, we called it a day.”

The next day the evaluation process continued. The horses were first driven quietly around in the fenced barnyard single and then ground driven there as a team. Doc drove them into position for hitching to the forecart several times but simply had them stand on either side of the tongue awhile without hitching up. All went extremely well. Later that day the students practiced hitching the team to a forecart repeatedly, and the horses were just fine with it. Doc explains, “We chose to hitch to and drive a two wheeled forecart before advancing to the four wheeled wagon later on. The horses were fine with each of the progressive tests, and we were able to resume our normal workshop curriculum.”

Standing Still Reliably

“I can’t emphasize enough,” says Doc, “the importance of teaching our driving horses to stop and stand still and to do so reliably. These are the most important lessons we’ll ever teach them. It should start when they’re young, and it needs to be reinforced every minute of every day that we’re with them. In addition to not letting them move their feet, we also need to manage their heads so they don’t get bridles, bits, halters, etc. hooked onto such things as harness parts, neck yokes, and shafts and perhaps rub or tear a bridle completely off.”

Doc’s friend and colleague Steve Wood teaches pleasure and competitive driving and trains horses to drive. Steve adds, “For a pair hitched to a carriage, almost 100 percent of tongues are self-supporting, (essentially suspended in the air), so the horses can’t be ground-driven into place. Instead, they’re typically led into position individually. This means the horses have to stand there for three or four minutes while the lines are attached and hitching is underway. So it’s even more the case that driving horses have to be trained to stand still reliably.”

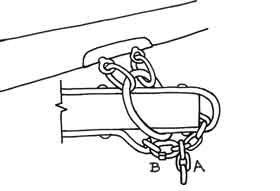

Diagram courtesy Doc Hammill.

Equipment and Harness Modifications

There are many things that could be discussed in the equipment and harness department that impact hitching and unhitching, but Doc would feel particularly negligent if he didn’t mention the importance of securing slip-on neck yokes and using what he calls a butt rope. “Many close calls, mishaps, wrecks, and injuries are caused when slip-on neck yokes that are not secured to the tongue accidentally slide off the end of the tongue,” says Doc. “This can happen more easily than most people think, both during hitching or unhitching and when actually driving. Consequently, all slip-on neck yokes should be secured to the tongue every time we hitch. My preferred way of securing them is shown in the diagram. Anything less than a 1/4-inch chain and a 5⁄16-inch quick link is not strong enough for forces that can be encountered.”

Doc continues, “One of the most common wrecks I’ve heard about over the years is horses spreading their hind ends and then getting head to head or even turning around and coming to the teamster. For this reason, I always recommend the use of a butt rope.“ (See “Key Techniques for Safe Confident Horses” in Rural Heritagevolume 36, number 5, October/November 2011.)

Ironclad Process for Hitching and Unhitching

Doc’s friend Steve Wood emphasizes the importance of a well-understood process for hitching. “Halfway hitched is the most dangerous time in driving, so you have to concentrate very carefully during that 90 seconds or you will forget something or do something incorrectly. A lot of people get distracted—‘Oh, wasn’t that a wonderful drive,’—and the conversation causes them to forget one strap or another. Because of multiple connections to the vehicle, with the single horse especially—with the hold backs and shaft wraps and traces—it’s easy to miss just one step that can have devastating consequences if not caught and corrected. And with young or green horses, when a driver forgets something, it changes the routine which can be stressful for the horse, heightening the possibility for an incident to occur.”

Steve continues, “Generally it’s another person who causes the distraction. On club drives, during family gatherings: the excitement can distract you as much as anything. Here’s my solution: I have a step-bystep check list. As a driver, hand that check list to your header. Make the header read off the list; it keeps him or her from starting up a conversation that might distract you during that critical 90 seconds. And remember that unhitching is the reverse of the hitching process; start at the bottom of the list and work back to the top. If people get distracted, especially when unhitching, they tend to do it backwards. When people are distracted, they tend to remember the first incorrect sequence (for hitching) rather than the second proper sequence (for unhitching). ”

Escape Plans

Especially when hitching the back end, when the driver is between the horses and the vehicle/load, our senses must be on high alert for anything that could lead to trouble. By taking such steps as hitching the inside trace chains before the outside chains, we can preserve our escape route should the horses take an unexpected step in any direction, putting us in jeopardy.

Doc explains, “Hooking the outside chain first then stretching to reach over it and hook (or unhook) the inside trace will put you way off balance. Were you to fall in between the trace chains behind the horses’ feet and in front of the vehicle/load, you’d be in extreme danger of being stepped on or run over. Standing with the lines between a horse and the vehicle near the tongue while someone else hooks or unhooks is also dangerous since a horse could fly back and crush you against the vehicle or load or go forward and pull the vehicle or load into you.”

Doc adds another important point about his extreme teaching moment, “It’s unlikely that I would have been able to hang onto and control both horses if I had not had halters and lead ropes on them. I was able to quickly undo the ropes from the hames and use them instead of the lines (which became useless because the fallen horse was lying on them). Without halters on AND lead ropes attached and easily accessible, we are at an extreme disadvantage if someone needs to get control of the heads.”

The Importance of Patience If we regularly hurry through our harnessing and hitching routine, it’s very easy to teach our horses an unintended lesson. If we hurriedly groom, harness, hitch, and drive off then we are teaching them to be impatient. Doing so sets us up for trouble when at some point the process is delayed for any reason and we really need to have them stand and wait rather than go.

Doc shares, “There are exercises I use regularly for helping horses practice patience, relaxation, and standing still. For instance, I ground drive them into position on the tongue but don’t hitch anything up. I wait and concentrate on having them stand there patiently for varying lengths of time before hitching. Sometimes I even drive them away without hitching so they become accepting of whatever I choose to ask for rather than start assuming they know what will happen next. However, once we start to hitch up (or unhitch), it’s important that we follow through to completion in an efficient but relaxed way without distractions or delays.”

Doc continues, “Once you are completely hitched, driving off right away sets a very bad precedent. I have often heard my good friend, master teamster, and horsemanship clinician John Erskine share a story with students. Another teamster whom John admired smoked a pipe. Every time after this man hitched up his team he would sit on the wagon, clean out his pipe, refill it, light it, and get it going. Only then would he ask his horses to go. John’s advice to students is not to smoke a pipe, but rather to take the time it would take to light a pipe before asking horses to go after they get them hitched. John assures them that their horses will become more and more patient and safer and safer if they do so, and that if they don’t, the horses will go the other way. It’s great advice for when we unhitch as well.”

In Hindsight

Doc concludes, “This incident came extremely close to being a disaster. If I had not been able to unhook the neck yoke to free the horses from the wagon, and/or if I had not been able to hold on to the horses and keep them from running off with or without the wagon, the potential for more significant lasting psychological effects and possibly physical injury to the horses would have been great. Though we were fortunate, I still fully expect the horses involved to be more anxious and concerned when they experience storm conditions in the future than they were before this experience.

“In hind sight, do I wish the horses had been tied up while I was hitching them for that particular demonstration? Yes, of course. The reason I show people how to do it alone and untied is because it is something that we and the horses need to know how to do. Sooner or later it may be unavoidable. However, when I’m demonstrating and explaining the process of hitching and unhitching, part of my attention is distracted from the horses and the process is slowed down, so in the future I’ll consider demonstrating the technique with the horses tied and let the students imagine that they aren’t.”

Steve Wood operates, with his wife Cathy, Wild Wood Sleigh and Carriage in Elk River, Minnesota.

Jenifer Morrissey works her draft ponies in Gould, Colorado.

This article appeared in the June/July 2012 issue of Rural Heritage magazine.